Exploring Bit-Flipping Attacks on CBC Block Cipher Mode in Cryptography

22 Oct 2017

.

tech

.

Comments

#security

#redteam

#crypto

Let’s explore how attackers can exploit vulnerabilities in crypto primitives. Specifically, we will dive into bit-flipping attacks on CBC block cipher mode. Assuming familiarity with CBC’s inner workings (if not, refer to the post on Padding Oracle attack), we’ll demonstrate how simple it is to carry out such an attack.

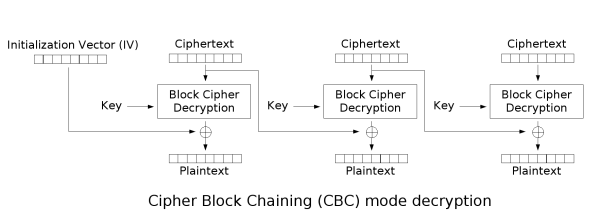

Let’s take a closer look at CBC decryption:

Note that in CBC decryption, each ciphertext block is XORed with the output of the next block. This step is crucial in recovering the final plaintext of the block, as the encryption algorithm chains the blocks to scramble the end ciphertext. Without this chaining process, there would be a 1-1 correlation between the plaintext byte and the ciphertext byte, leading to significant information leakage about the plaintext.

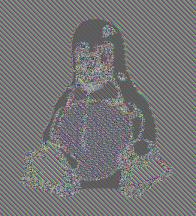

Here’s an example of an unchained block encryption applied to an original image:

Now, you can better understand the ramifications of “leaking a lot of information.”

Returning to the decryption diagram, if we flip a bit in a ciphertext block, we can flip the output plaintext bit of the subsequent block. Why? Because XOR is a bit operation that is associative, and XOR-ing with ‘1’ changes a ‘0’ to ‘1’ and vice versa, per XOR’s definition.

However, what are the consequences of flipping a bit in the final plaintext? They are numerous! For example, suppose a server sends an encrypted cookie to the client:

"admin=0"

The first mistake was giving authorization control to the client. When the client can manipulate information, including ciphertexts, security vulnerabilities arise.

For instance, flipping the 7th byte of the IV (in cases where the output ciphertext is only two blocks long) allows us to flip the 7th bit of the first block of plaintext computed by the server. The result is:

"admin=1"

In case the server doesn’t authenticate the ciphertext that we submit, by using a MAC, and neglects to carry out additional authorization control on its side, we can escalate privileges and become an admin ourselves!

Now let’s examine how simple it is to execute this attack:

require 'openssl'

class UnauthenticatedEncryption

def encrypt(plaintext)

cipher = OpenSSL::Cipher::AES.new(256, :CBC)

cipher.encrypt

@key = cipher.random_key

iv = cipher.random_iv

ciphertext = cipher.update(plaintext) + cipher.final

return iv + ciphertext

end

def decrypt(ciphertext)

decipher = OpenSSL::Cipher::AES.new(256, :CBC)

decipher.decrypt

decipher.key = @key

decipher.iv = ciphertext[0..15]

plaintext = decipher.update(ciphertext[16..(ciphertext.length - 1)]) + decipher.final

return plaintext

end

end

plaintext = 'admin=0'

unauthenticatedEncryption = UnauthenticatedEncryption.new()

intercepted_ciphertext = unauthenticatedEncryption.encrypt(plaintext)

intercepted_ciphertext[6] = (intercepted_ciphertext.bytes[6] ^ 0x01).chr

new_plaintext = unauthenticatedEncryption.decrypt(intercepted_ciphertext)

puts new_plaintext

# admin=1

One might assume that flipping only one bit is easy, but flipping multiple bits to transform a “false” into a “true” is also a simple task. The process merely involves flipping additional bits.

To prevent this type of attack, one solution is to use the MAC-then-encrypt scheme or to use a block cipher mode that provides authentication automatically. As always, all user input must be authenticated before being processed, like the Cryptographic Doom Principle states.